The always-thoughtful John E. Roemer gave a talk on "The Ideological and Political Roots of American Inequality" at a conference last February. The talk is available as a working paper here; a revised version of the talk appears as an article with the same name in the September-October issue of Challenge magazine, which is available on-line if your library has a subscription. I quote here from the working paper version.

A First Argument for Inequality: Individuals Deserve to Benefit from Their Endowments

The first argument that Roemer considers for inequality is "an ethical one, that individuals deserve to benefit from what nature and nurture endows them with ... The first argument is presented in its most compelling form by thephilosopher Robert Nozick, who in his 1974 book, Anarchy, State and Utopia, advanced the idea that a person has a right to own himself and his powers, and to benefit by virtue of any good luck that may befall him, such as the luck of being born into a rich family, or in a rich nation. ... Nozick is the first the admit that actual capitalist economies are not characterized by historical sequences of legitimate, voluntary exchanges: there is much coercion, corruption, and theft in the history of all societies. But Nozick’s point is that one can imagine a capitalism with a clean history, in which vastly unequal endowments of wealth are built up entirely from exchanges between highly talented, well educated people and simple, unskilled ones, and this unequal result is ethically acceptable if one accepts the premise that one has a right to benefit by virtue of one’s endowments – biological, familial, and social – or so he claims."

Responses from Rawls and Dworkin to this first argument

"The philosophical response to Robert Nozick’s libertarianism came primarily from two political philosophers, John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin. ... Rawls attempted to construct an argument that, if rational, self-interested beings were shielded from the knowledge of the luck they would sustain in the birth lottery, which assigns genes and families, they would opt for a highly equal distribution of wealth – indeed, for that distribution which maximizes the wealth that the poorest class of people would have. . ... The error in Rawls’s argument that those in an original position, behind a veil of ignorance, would choose a highly equal distribution of income, came from his assumption that the decision makers postulated to occupy this position were completely self-interested. Self-interested individuals may be willing to take some risk in the birth lottery – they may be willing to accept some possibility of an unlucky draw in return for the possibility of a lucky draw. ... This does not mean that a strongly equalizing tax system is ethically wrong: but to justify it with the kind of argument Rawls wished to

construct requires that individuals care at least to some degree about others. Rawls’s attempt to derive equality of results from premises of rationality and self-interest fails. ... There was another aspect of Rawls’s theory that was unattractive to some: there was no evident place in it for the role of personal responsibility and accountable choice. ... Ronald Dworkin, in 1981, published a pair of articles which addressed this problem in a radical, new way. He advocated what he dubbed ‘resource equality’ ... In Dworkin’s view, people should be held responsible for their preferences, but not for their resources – where resources include many of the goods that Rawls called morally arbitrary, such as genetic endowments and the social and familial circumstances of one’s childhood. ... Thus, a degree of equality was recommended that was less than Rawlsian, but far more than exists in most advanced democracies today."

A Second Argument for Inequality: Incentives

The second argument that Roemer considers about inequality is "the instrumental one: that only by allowing highly talented persons to keep a large fraction of the wealth that they help in creating will that creativity flourish, which redounds to the benefit of all, through what is informally called the trickle-down process. In a word, material incentives are necessary to engender the creativity in that small fraction of humanity who have the potential for it, and state interventions, primarily through income taxation, which reduce those material rewards, will kill the goose that lays the golden eggs."

A Response: Contrasting The Market Role in Coordination and Incentives

"Economists have long realized that markets perform two functions: they coordinate economic activity, and they provide incentives for the development of skills and innovations. It is not easy to give a definition which distinguishes precisely between these two functions, but there is no question that a conceptual distinction exists. ... In the last thirty or forty years, the economic theorist’s view of the market has changed, from being an institution which performs primarily a coordination function to one that is primarily harnessing incentives. Indeed, the old definition of micro-economics was the study of how to allocate scarce resources to competing needs. This is entirely a coordination view. ...

It may surprise you to hear that the phrase ‘principal-agent problem’ was only introduced into economics in 1973, in an article by Steven Ross. In the principal-agent problem, coordination is not the primary issue – rather, a principal must design a contract to extract optimal performance from an agent whose behavior he cannot perfectly observe. This is par excellence an incentive problem. ...

"The punch line I am proposing is this: to the extent that the market is primarily a device for coordination, taxation can redistribute income without massive efficiency costs. But if the market is primarily a device for harnessing incentives, the efficiency costs of redistribution may be high. ..Although economic theory has shifted on this question during the last generation, it is far from obvious that the shift is empirically justified – by which I mean, we do not know that the market’s role in incentive provision is as important as current economic theory contends. ..."

"I have argued that these high incomes are inefficient, because of risk-taking externalities that they induce, that they are unnecessary for incentive provision, and that they create a class with disproportionate political power. Finally, there is the very important negative externality of the creation of a social ethos which worships wealth. ... In sum, the positive social value of the institution of extremely high salaries that the leaders of the corporate world, and in particular, of the financial sector, receive, is a big lie. It may well be a competitive outcome, but it is a market failure which could be corrected by regulation or legislation."

A Third Argument for Inequality: Policy Futility

"A third argument for inequality, which is currently most prevalent in the United States, is one of futility: even if the degree of inequality that comes with laissez-faire is not socially necessary in the sense that the incentive argument claims, attempts by the state to reduce it will come to naught, because the government is grossly incompetent, inefficient, or corrupt. ... This is, I think, a particularly American view, so it is probably not appropriate to spend much time on it here."

How Does Inequality Affect Economic Growth?

Historically, many economists believed that a healthy degree of economic inequality was good for economic growth. Branko Milanovic explains in "More or Less":

In "Why Aren't All Countries Rich?", Jessie Romero of the Richmond Federal Reserve discusses some patterns in this literature. As this figure shows, the Latin America and the Sub-Saharan Africa regions have consistently had the greatest degree of inequality.

Thus, given the relatively slow growth rates in these regions in the 1980s and 1990s, and the comparatively fast growth rates in more-equal Asia, economic research at that time had often claimed a connection between greater inequality and slower growth. However, in 1996, Klaus Deininger and Lyn Squire ("A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality", World Bank Economic Review, 10(3): 565-91, 1996) pointed out that this kind of comparison across countries didn't control sufficiently for other factors that could vary across regions and countries, like variations in political and social institutions or in initial level of development. In their analysis, with these kinds of factors taken into account, the degree of economic inequality didn't seem to influence subsequent growth.

More recently, Andrew G. Berg and Jonathan D. Ostry have been taking a look at the relationship between inequality and the length of periods of economic growth, and their readable summary of their results is here. They write (citations and references to charts have been cut):

In their work, interestingly enough, income inequality and trade openness are major factors in determining how long periods of growth will last, while political institutions and foreign direct investment are of intermediate importance, and external debt and exchange rate competitiveness are of little importance.

"The view that income inequality harms growth—or that improved equality can help sustain growth—has become more widely held in recent years. ... Historically, the reverse position—that inequality is good for growth—held sway among economists. The main reason for this shift is the increasing importance of human capital in development. When physical capital mattered most, savings and investments were key. Then it was important to have a large contingent of rich people who could save a greater proportion of their income than the poor and invest it in physical capital. But now that human capital is scarcer than machines, widespread education has become the secret to growth. And broadly accessible education is difficult to achieve unless a society has a relatively even income distribution. Moreover, widespread education not only demands relatively even income distribution but, in a virtuous circle, reproduces it as it reduces income gaps between skilled and unskilled labor. So economists today are more critical of inequality than they were in the past."The economic literature on the possible causal relationship between inequality and growth seems to have gone from arguing for such a connection in the 1980s and early 1990s, to arguing that the connection wasn't so important in the mid-1990s, and now back to arguing that it may be important.

In "Why Aren't All Countries Rich?", Jessie Romero of the Richmond Federal Reserve discusses some patterns in this literature. As this figure shows, the Latin America and the Sub-Saharan Africa regions have consistently had the greatest degree of inequality.

Thus, given the relatively slow growth rates in these regions in the 1980s and 1990s, and the comparatively fast growth rates in more-equal Asia, economic research at that time had often claimed a connection between greater inequality and slower growth. However, in 1996, Klaus Deininger and Lyn Squire ("A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality", World Bank Economic Review, 10(3): 565-91, 1996) pointed out that this kind of comparison across countries didn't control sufficiently for other factors that could vary across regions and countries, like variations in political and social institutions or in initial level of development. In their analysis, with these kinds of factors taken into account, the degree of economic inequality didn't seem to influence subsequent growth.

More recently, Andrew G. Berg and Jonathan D. Ostry have been taking a look at the relationship between inequality and the length of periods of economic growth, and their readable summary of their results is here. They write (citations and references to charts have been cut):

"Most thinking about long-run growth assumes implicitly that development is something akin to climbing a hill, that it entails more or less steady increases in real income, punctuated by business cycle fluctuations. ... The experiences in developing and emerging economies, however, are far more varied. In some cases, the experience is like climbing a hill. But in others, the experience is more like a roller coaster. Looking at such cases, Pritchett and other authors have concluded that an understanding of growth must involve looking more closely at the turning points—ignoring the ups and downs of growth over the horizon of the business cycle, and concentrating on why some countries are able to keep growing for long periods whereas others see growth break down after just a few years, followed by stagnation or decay. A systematic look at this experience suggests that igniting growth is much less difficult than sustaining it. Even the poorest of countries have managed to get growth going for several years, only to see it peter out. Where growth laggards differ from their more successful peers is in the degree to which they have been able to sustain growth for long periods of time."

In their work, interestingly enough, income inequality and trade openness are major factors in determining how long periods of growth will last, while political institutions and foreign direct investment are of intermediate importance, and external debt and exchange rate competitiveness are of little importance.

0

comments

Labels:

inequality,

poverty

Herbert Hoover, Deficit-Spender: Correcting John Judis in The New Republic

In the October 6 cover story for The New Republic, titled "Doom!", John B. Judis admonishes readers to beware the economic lessons of the 1930s--and then proceeds to make a number of incorrect statements about what happened in the 1930s.

In the third paragraph, Judis pats himself on the back for asking Mitt Romney a tough question. Judis asked: "I want to ask you something about history.You know, when Herbert Hoover had to face a financial crisis and then unemployment, his strategy was to balance the budget and cut spending, and that made things worse. When Roosevelt came in, unemployment was twenty-five and went to fourteen percent by 1937. With deficits. Aren't you repeating the Hoover mistake?"

Before listing the various mistakes here, the actual spending, debt, and deficit numbers starting in 1930, both in nominal terms and as a share of GDP, are readily available in the Historical Tables volume that is published each year with the president's proposed federal budget. All numbers I quote here are from the "Historical Tables" volume in the 2012 budget. From that source, you can easily confirm the following facts:

1) Hoover's budget strategy over his term of office was not to balance the budget. The budget ran a small deficit of -.6% of GDP in 1931, followed by a much larger deficits of 4.0% of GDP in 1932 and 4.5% of GDP in fiscal year 1933 (which, as Judis points out at a different point in his discussion, started in June 1932 and was thus mostly completed before Roosevelt took office in 1933).

2) Hoover did not cut spending. In nominal terms, federal spending went from $3.3 billion (!) in 1930 to $4.6 billion in 1933. Given price deflation during that time, the real increase in government spending would have been larger. With the economy declining in size, federal outlays more than doubled from 3.4% of GDP in 1930 to 8.0% of GDP in fiscal year 1933.

3) Because of this pattern, it would be hard to find an economic historian to argue that fiscal tightness was a significant factor in worsening the Great Depression from 1929 to 1932. The economic literature has for half a century focused on how overly tight monetary policy deepened the Depression, and has noted at length how the dysfunction of monetary policy at that time worked through banks and the financial system and through the exchange rate to hinder the economy. It would also be hard to find an economic historian to argue that the primary reason for the drop in unemployment rates from 1933 to 1937 was a surge of expansionary fiscal policy.

4) During the 1932 presidential campaign, Franklin Roosevelt promised to wipe out the Hoover budget deficits and instead to run a balanced budget. In his first few months after taking office, FDR tried to put this policy into effect--before soon abandoning it. For a source, here is a description from the quick history at the Franklin D. Roosevelt American Heritage Center Museum: "Roosevelt promised in his 1932 campaign that he would end the deficits that had plagued the Hoover administration and restore a balanced budget. This he never did, and eventually he would come to consider deficit spending a useful and necessary response to recession. In 1933, however, he remained committed to fiscal orthodoxy, and on 10 March he asked Congress to pass legislation cutting government salaries and veterans' benefits. Both Houses passed the Economy Act within days, despite protests from some progressives who argued correctly that the measure would add to the deflationary pressures on the economy... The New Deal soon departed from these conservative beginnings."

It gets worse. Judis writes (a bit smugly) how Romney evaded his question, and then writes: "But he [Romney] seemed to be suggesting that the premise of my question was flawed because deficits are much larger today and will probably continue unabated. And they are larger--but that is because our GDP and government are also larger."

But deficits as a share of GDP are much larger now than than they were in the Great Depression. The two biggest deficits in the 1930s were 5.5% of GDP in 1936 and 5.9% of GDP in 1934. The budget deficit was 10.0% of GDP in 2009, 8.9% of GDP in 2010, and (estimated) 10.9% of GDP in 2011.

Judis believes that additional fiscal stimulus is warranted. I supported both the Bush fiscal stimulus package in 2008 and the Obama stimulus package in 2009, although I had some disagreements with their design and targetting. While I do think it's tremendously important to get the U.S. deficits under control in the middle term, I wouldn't try to slash the deficit in the short run with unemployment still up around 9%.

But the notion that the Great Depression was an example of highly active fiscal stimulus and the Great Recession was not is upside-down. Recent years have seen a far larger fiscal stimulus in response to a lower unemployment rate than in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt faced unemployment rates of 25% and continued the Hoover policy of budget deficits, running deficits no larger than 5.9% of GDP and more usually in the range of 3-4% of GDP through the 1930s. During the Great Recession, the U.S. economy experienced unemployment of nearly 10%, and has responded with fiscal stimulus on the order of 10% of GDP.

And the elephant in the room, which Judis doesn't discuss, is the accumulation of debt. After all of the deficits of the 1930s, the total ratio of federal debt held by the public still totaled only 44.2% of GDP in 1940. Throughout the 1930s, the federal government had a lot of capacity to borrow--and could then still ramp borrowing much higher to finance the fighting of World War II. But in 2011, total federal debt held by the public is an estimated 72% of GDP. Looking ahead over the next decade, the federal government has a lot less capacity to borrow.

ADDED: For a follow-up on the post on October 4, see my post on More Herbert Hoover: Father of the New Deal.

In the third paragraph, Judis pats himself on the back for asking Mitt Romney a tough question. Judis asked: "I want to ask you something about history.You know, when Herbert Hoover had to face a financial crisis and then unemployment, his strategy was to balance the budget and cut spending, and that made things worse. When Roosevelt came in, unemployment was twenty-five and went to fourteen percent by 1937. With deficits. Aren't you repeating the Hoover mistake?"

Before listing the various mistakes here, the actual spending, debt, and deficit numbers starting in 1930, both in nominal terms and as a share of GDP, are readily available in the Historical Tables volume that is published each year with the president's proposed federal budget. All numbers I quote here are from the "Historical Tables" volume in the 2012 budget. From that source, you can easily confirm the following facts:

1) Hoover's budget strategy over his term of office was not to balance the budget. The budget ran a small deficit of -.6% of GDP in 1931, followed by a much larger deficits of 4.0% of GDP in 1932 and 4.5% of GDP in fiscal year 1933 (which, as Judis points out at a different point in his discussion, started in June 1932 and was thus mostly completed before Roosevelt took office in 1933).

2) Hoover did not cut spending. In nominal terms, federal spending went from $3.3 billion (!) in 1930 to $4.6 billion in 1933. Given price deflation during that time, the real increase in government spending would have been larger. With the economy declining in size, federal outlays more than doubled from 3.4% of GDP in 1930 to 8.0% of GDP in fiscal year 1933.

3) Because of this pattern, it would be hard to find an economic historian to argue that fiscal tightness was a significant factor in worsening the Great Depression from 1929 to 1932. The economic literature has for half a century focused on how overly tight monetary policy deepened the Depression, and has noted at length how the dysfunction of monetary policy at that time worked through banks and the financial system and through the exchange rate to hinder the economy. It would also be hard to find an economic historian to argue that the primary reason for the drop in unemployment rates from 1933 to 1937 was a surge of expansionary fiscal policy.

4) During the 1932 presidential campaign, Franklin Roosevelt promised to wipe out the Hoover budget deficits and instead to run a balanced budget. In his first few months after taking office, FDR tried to put this policy into effect--before soon abandoning it. For a source, here is a description from the quick history at the Franklin D. Roosevelt American Heritage Center Museum: "Roosevelt promised in his 1932 campaign that he would end the deficits that had plagued the Hoover administration and restore a balanced budget. This he never did, and eventually he would come to consider deficit spending a useful and necessary response to recession. In 1933, however, he remained committed to fiscal orthodoxy, and on 10 March he asked Congress to pass legislation cutting government salaries and veterans' benefits. Both Houses passed the Economy Act within days, despite protests from some progressives who argued correctly that the measure would add to the deflationary pressures on the economy... The New Deal soon departed from these conservative beginnings."

It gets worse. Judis writes (a bit smugly) how Romney evaded his question, and then writes: "But he [Romney] seemed to be suggesting that the premise of my question was flawed because deficits are much larger today and will probably continue unabated. And they are larger--but that is because our GDP and government are also larger."

But deficits as a share of GDP are much larger now than than they were in the Great Depression. The two biggest deficits in the 1930s were 5.5% of GDP in 1936 and 5.9% of GDP in 1934. The budget deficit was 10.0% of GDP in 2009, 8.9% of GDP in 2010, and (estimated) 10.9% of GDP in 2011.

Judis believes that additional fiscal stimulus is warranted. I supported both the Bush fiscal stimulus package in 2008 and the Obama stimulus package in 2009, although I had some disagreements with their design and targetting. While I do think it's tremendously important to get the U.S. deficits under control in the middle term, I wouldn't try to slash the deficit in the short run with unemployment still up around 9%.

But the notion that the Great Depression was an example of highly active fiscal stimulus and the Great Recession was not is upside-down. Recent years have seen a far larger fiscal stimulus in response to a lower unemployment rate than in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt faced unemployment rates of 25% and continued the Hoover policy of budget deficits, running deficits no larger than 5.9% of GDP and more usually in the range of 3-4% of GDP through the 1930s. During the Great Recession, the U.S. economy experienced unemployment of nearly 10%, and has responded with fiscal stimulus on the order of 10% of GDP.

And the elephant in the room, which Judis doesn't discuss, is the accumulation of debt. After all of the deficits of the 1930s, the total ratio of federal debt held by the public still totaled only 44.2% of GDP in 1940. Throughout the 1930s, the federal government had a lot of capacity to borrow--and could then still ramp borrowing much higher to finance the fighting of World War II. But in 2011, total federal debt held by the public is an estimated 72% of GDP. Looking ahead over the next decade, the federal government has a lot less capacity to borrow.

ADDED: For a follow-up on the post on October 4, see my post on More Herbert Hoover: Father of the New Deal.

0

comments

Labels:

budget deficits,

Great Depression

Global Equality and the Lucas Horse Race

It is possible that although inequality within many countries is rising, global inequality is actually falling. After all, a number of countries with lower levels of per capita income, like China and India, have been experiencing rapid growth. Perhaps from a global viewpoint, the gap between high and low incomes is diminishing even though within countries, that gap has been rising.

In the Winter 2000 issue of my own Journal of Economic Perspectives, Robert E. Lucas

contributed "Some Macroeconomics for the 21st Century." He offers a horse-racing metaphor that I have found useful in explaining the rise in global inequality over the last couple of centuries--and he predicts that the 21st century will be one of greater global equality. Here's Lucas:

Milanovic writes: "Global inequality seems to have declined from its high plateau of about 70 Gini points in 1990–2005 to about 67–68 points today. This is still much higher than inequality in any single country, and much higher than global inequality was 50 or 100 years ago. But the likely downward kink in 2008—it is probably too early to speak of a slide—is an extremely welcome sign. If sustained (and much will depend on China’s future rate of growth), this would be the first decline in global inequality since the mid-19th century and the Industrial Revolution.

One could thus regard the Industrial Revolution as a “Big Bang” that set some countries on a path to higher income, and left others at very low income levels. But as the two giants—India and China—move far above their past income levels, the mean income of the world increases and global inequality begins to decline."

In the Winter 2000 issue of my own Journal of Economic Perspectives, Robert E. Lucas

contributed "Some Macroeconomics for the 21st Century." He offers a horse-racing metaphor that I have found useful in explaining the rise in global inequality over the last couple of centuries--and he predicts that the 21st century will be one of greater global equality. Here's Lucas:

"We consider real production per capita, in a world of many countries evolving through time. For modelling simplicity, take these countries to have equal populations. Think of all of these economies at some initial date, prior to the onset of the industrial revolution. Just to be specific, I will take this date to be 1800. Prior to this date, I assume, no economy has enjoyed any growth in per capita income—in living standards—and all have the same constant income level. I will take this pre-industrial income level to be $600 in 1985 U.S. dollars, which is about the income level in the poorest countries in the world today and is consistent with what we know about living standards around the world prior to the industrial revolution. We begin, then, with an image of the world economy of 1800 as consisting of a number of very poor, stagnant economies, equal in population and in income.What is the evidence on global inequality? Branko Milanovic offers a useful figure, where inequality is measured by the Gini coefficient. For those not familiar with this term, the quick intuition is that it is a measure of inequality where 0 represents complete equality of income and 100 represents complete inequality (one person has all the resources). Here is a figure showing Gini coefficients for relatively equal Sweden, the less equal U.S. economy, the still-less-equal Brazilian economy, and the world economy.

"Now imagine all of these economies lined up in a row, each behind the kind of mechanical starting gate used at the race track. In the race to industrialize that I am about to describe, though, the gates do not open all at once, the way they do at the track. Instead, at any date t a few of the gates that have not yet opened are selected by some random device. When the bell rings, these gates open and some of the economies that had been stagnant are released and begin to grow. The rest must wait their chances at the next date, t + 1. In any year after 1800, then, the world economy consists of those countries that have not begun to grow, stagnating at the $600 income level, and those countries that began to grow at some date in the past and have been growing every since.

The first is that the first economy to begin to industrialize—think of the United Kingdom, where the industrial revolution began—simply grew at the constant rate a from 1800 on. I chose the value α = .02 which, as one can see from the top curve on the figure, implies a per capita income for the United Kingdom of $33,000 (in 1985 U.S. dollars) by the year 2000. ...

So much for the leading economy. The second assumption ... is that an economy that begins to grow at any date after 1800 grows at a rate equal to a α = .02, the growth rate of the leader, plus a term that is proportional to the percentage income gap between itself and the leader. The later a country starts to grow, the larger is this initial income gap, so a later start implies faster initial growth. But a country growing faster than the leader closes the income gap, which by my assumption reduces its growth rate toward .02. Thus, a late entrant to the industrial revolution will eventually have essentially the same income level as the leader, but will never surpass the leader’s level. ...

"Ideas can be imitated and resources can and do flow to places where they earn the highest returns. Until perhaps 200 years ago, these forces sufficed to maintain a rough equality of incomes across societies (not, of course, within societies) around the world. The industrial revolution overrode these forces for equality for an amazing two centuries: That is why we call it a “revolution.” But they have reasserted themselves in last half of the 20th century, and I think the restoration of inter-society income equality will be one of the major economic events of the century to come."

Milanovic writes: "Global inequality seems to have declined from its high plateau of about 70 Gini points in 1990–2005 to about 67–68 points today. This is still much higher than inequality in any single country, and much higher than global inequality was 50 or 100 years ago. But the likely downward kink in 2008—it is probably too early to speak of a slide—is an extremely welcome sign. If sustained (and much will depend on China’s future rate of growth), this would be the first decline in global inequality since the mid-19th century and the Industrial Revolution.

One could thus regard the Industrial Revolution as a “Big Bang” that set some countries on a path to higher income, and left others at very low income levels. But as the two giants—India and China—move far above their past income levels, the mean income of the world increases and global inequality begins to decline."

0

comments

Labels:

growth,

inequality

The Kuznets Curve and Inequality over the last 100 Years

The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel first started being given in 1969, the backlog of worthy economists who were deserving of the prize was very large. Thus, it was a considerable compliment when the third Nobel prize given in economics went to Simon Kuznets in 1971. Among other major contributions, Kuznets was one of the primary contributors to thinking through the issues of constructing national income accounts and GDP. But my focus here is on a theory which grew out of his Presidential Address on "Economic Growth and Income," delicvered to the American Economic Association in 1954 and published in the March 1955 issue of the American Economic Review. This lecture led economists to speak of a "Kuznets curve."

Here's a short explanation of the logic behind the Kuznets curve from Branko Milanovic in the September 2011 issue of Finance and Development has several articles with perspectives on inequality. "The Kuznets curve, formulated by Simon Kuznets in the mid-1950s, argues that in preindustrial societies, almost everybody is equally poor so inequality is low. Inequality then rises as people move from low-productivity agriculture to the more productive industrial sector, where average income is higher and wages are less uniform. But as a society matures and becomes richer, the urban-rural gap is reduced and old-age pensions, unemployment benefits, and other social transfers lower inequality. So the Kuznets curve resembles an upside-down `U.'"In 2011, of course, the notion that inequality always declines as an economy grows no longer seems plausible. Later in the same issue, Facundo Alvaredo offers some nice figures of trends in inequality around the world since about 1900, where inequality is measured by the share of total income going to the top 1% of the income distribution. There are four figures, each with a group of countries. "In Western English-speaking countries, inequality declined until about 1980 and then began to grow again. Continental European countries and Japan had a decline until about 1950; since then income distribution has leveled. For Nordic and Southern European countries, the drop in inequality in the

early part of the century was much more pronounced than the rebound in the late part of the period. Developing countries show initial declines in inequality followed by a leveling off in some cases and an increase in inequality in others."

For a series of posts in July on the extent and causes of U.S. income inequality, see:

How high is U.S. income inequality?

Causes of Inequality: Supply and Demand for Skilled Workers

How the U.S. Has Come Back to the Pack in Higher Education

An Inequality Parade

0

comments

Labels:

inequality

The Global Biomedical Industry

Ross C. DeVol, Armen Bedroussian, and Benjamin Yeo write on "The Global Biomedical Industry: Preserving U.S. Leadership," which is available (with free registration) from the Milken Institute website. In this industry, they include pharmaceuticals, medical devices and equipment, and the accompanying research, testing, and medical labs. Some excerpts (footnotes deleted throughout):

The U.S. hasn't always been a leader in biomedical technologies

The shift to U.S. leadership in pharmaceuticals

The share of new chemical entities for the world as a whole produced by firms with a U.S. headquarters rose from about 31-32% in the 1970s and 1980s to 57% in the most recent decade. The U.S. share of global pharmaceutical R&D spending has risen to roughly half the world total over the last decade.

The U.S. has no guarantee of continuing its technological leadership

The U.S. advantage in regulatory processes and clinical trials is diminishing

The U.S. hasn't always been a leader in biomedical technologies

"Prior to 1980, European firms defined the industry, both in terms of market presence and in their ability to create and produce innovative new products. Historical advantages and an enviable concentration of resources fueled the success of firms in Germany, France, the U.K., and Switzerland. Japan had a presence in the industry as well. But beginning in the 1980s, the United States surged to the forefront of biomedical innovation. This sudden and remarkable shift was no accident: It was the result of strong policy positions taken by the federal government. The absence of price controls, the clarity of regulatory approvals, a thoughtful intellectual property system, and the ability to attract foreign scientific talent to outstanding research universities put the U.S. on top."

The shift to U.S. leadership in pharmaceuticals

The share of new chemical entities for the world as a whole produced by firms with a U.S. headquarters rose from about 31-32% in the 1970s and 1980s to 57% in the most recent decade. The U.S. share of global pharmaceutical R&D spending has risen to roughly half the world total over the last decade.

The U.S. has no guarantee of continuing its technological leadership

"The dominance enjoyed by the U.S. biomedical industry does not come with a long-term guarantee. The U.S. assumed the mantle of leadership by being the first to commercialize recombinant DNA research—and that achievement was made possible only because it had built an environment and infrastructure that allowed innovation to flourish. But if another nation duplicates or improves upon this formula by building a similar ecosystem and subsequently makes a pivotal scientific breakthrough in nanotechnology, personalized medicine, embryonic stem cell research, or some other cutting-edge field, it could tip the scales in the other direction. That scenario is a real possibility: While the U.S. led with 29.7 percent of nanotech-related patents granted between 1996 and 2008 (as measured by resident country of first-name inventor), China was a close second, with 24.3 percent of these patents. ... Pharmaceutical patents that credit at least one inventor in China or India rose four-fold between 1996 and 2006—China held 8.4 percent and India 5.5 percent of worldwide patents. Other countries in Asia and around the world are also making advances, among them Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, Australia, Canada, Brazil, and Chile. ... In stem cell science, other nations with sophisticated biomedical research infrastructure in place—including the U.K., Japan, France, Switzerland, and several others—have instituted more flexible government funding guidelines than the U.S. These nations have been attracting leading embryonic stem-cell researchers from countries with more restrictive policies."

The U.S. advantage in regulatory processes and clinical trials is diminishing

"While the FDA has seen an increase in average review times, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been streamlining. After declining to 12.3 months in 2007, the average FDA review time for new drugs increased to 17.8 months in 2008. This number does fluctuate, and while it improved in 2009, anecdotal evidence suggests that the 2010 numbers will reflect a slowdown. Meanwhile, the EMA has reduced its drug approval time to 15.8 months. ... Medical device approvals from the FDA have become even more problematic than drug approvals. The EMA approves some devices in almost half the time it takes for similar approvals by the FDA. ..."

"Innovation is the driver of ultimate market success, and the U.S. originated more than half of the leading 75 global medicines (or new active substances as measured by worldwide sales) in 2009. Clinical trials are a critical step in that process as well as a benchmark that reflects the degree of innovation taking place in a given location. As of early 2011, 50.9 percent of all clinical trials in the world were being held in the U.S. Despite the size of its clinical capacity, the average relative annual growth in the U.S. declined by 6.5 percent between 2002 and 2006. Meanwhile, trial growth, particularly among emerging nations, outpaced the U.S. during that time. In countries

like China and India, average relative annual growth increased by 47 percent and nearly 20 percent, respectively. ...

Clinical trials are a lengthy and expensive step in the U.S., but other countries are finding ways to make trials faster and more cost-effective.As shown below, emerging markets such as China and India can conduct clinical trials for about half the cost of those in the U.S. Russia is even more cost-effective and offers experienced researchers trained in “Good Clinical Practice” standards set by the International Conference on Harmonization. In Russia, 8,000 (or 1 in 86) physicians are involved in clinical trials. ... In addition to cost advantages, these emerging nations also have vast populations that make it faster and easier to enroll the required number of patients in a trial. According to the Association of Clinical Research Organizations, completely enrolling patients in a phase III clinical trial for a cancer treatment would take almost six years in the U.S. However, if companies have access to a global pool of patients, the process could be cut to less than two years. These new international options for clinical trials pose clear benefits to U.S. firms: They can conduct some

portions of their testing overseas, reducing their time and costs while gaining valuable knowledge about how to adjust their compounds as they move through the U.S. approval process. An estimated 40 to 65 percent of clinical trials that investigate FDA-regulated products are conducted outside the U.S., although many of these trials are for comparative purposes.

"But taking a longer view, this trend raises a cautionary flag for U.S. competitiveness. Clinical trials require scientific staff, and as other nations develop this specialty, they are amassing high-value experts, infrastructure, and technical capacity. U.S. firms will increasingly have to fight for their share of a finite pool of global talent and investment dollars, and the U.S. economy may lose high-wage jobs. In 1997, according to the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, about 86 percent of FDA-registered principal investigators were based in the United States, but by 2007, that was down to only about 54 percent."

0

comments

Labels:

biomedical,

innovation

How Are Global Investors Allocating their Assets?

The second chapter of the IMF's most recent Global Financial Stability Report is about "Long-Term Investors and their Asset Allocation: Where Are They Now?" Here are a few of the main themes, with citations and footnotes eliminated throughout:

What are the big trends?

"To set the stage, the longer-term developments in global asset allocation show three main trends: (i) a gradual broadening of the distribution of assets across countries, implying a globalization of portfolios with a slowly declining home bias; (ii) a long-term decline in the share of assets held by pension funds and insurance companies in favor of asset management by investment companies; and (iii) the increasing importance of the official sector in global asset allocation through sovereign wealth funds and managers of international reserves."

Does the inflow of capital to emerging markets pose danger if there is a sudden stop or reversal?

"While the trend toward longer-term investment in emerging markets is likely to continue, shocks to

growth prospects or other drivers of private investment could lead to large investment reversals. The

structural trend of investing in emerging market assets accelerated following the crisis, driven mostly by relatively good economic and investment outcomes. Still, the sensitivity analysis in this chapter showed that a negative shock to growth prospects in emerging markets could potentially lead to flows out of emerging market equities and bonds. These flows could reach a scale similar to—or even larger than—the outflows these countries experienced during the financial crisis. ... Policymakers should prepare for the possibility of a pullback from their markets in order to mitigate the risk of potentially disruptive liquidity problems, especially if market depth may not be sufficient to avoid large price swings. Emerging market policymakers ... should prepare contingency plans to maintain liquidity in asset markets during periods of market turmoil, perhaps using sovereign asset managers as providers of liquidity as other investors exit, as some did during the crisis ...

Will countries start taking more risk with foreign exchange reserves?

"As heightened risk awareness and regulatory initiatives push private investors to hold “safer” assets, sovereign asset managers may take on some of the longer-term risks that private investors now avoid. ... However, global foreign exchange reserve holdings (excluding gold) have grown so fast in recent

years that their size for many countries now exceeds that needed for balance of payments and monetary purposes. ... Therefore, an increasing share of reserves could be available for potential investment in less liquid and longer-term risk assets. A new IMF estimate puts core reserves needed for balance of payments purposes in emerging market economies at $3.0–$4.4 trillion, leaving $1.0–$2.3 trillion potentially available to be invested beyond the traditional mandate of reserve managers, in a manner more like that of SWFs."

What about sovereign wealth funds?

"Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) hold some $4.7 trillion in assets ... while international foreign exchange reserves amount to $10 trillion. Taken together, the value of assets in SWFs and foreign exchange reserves is equal to about one-fourth of the assets under management of private institutional investors. ..."

What are the big trends?

"To set the stage, the longer-term developments in global asset allocation show three main trends: (i) a gradual broadening of the distribution of assets across countries, implying a globalization of portfolios with a slowly declining home bias; (ii) a long-term decline in the share of assets held by pension funds and insurance companies in favor of asset management by investment companies; and (iii) the increasing importance of the official sector in global asset allocation through sovereign wealth funds and managers of international reserves."

Does the inflow of capital to emerging markets pose danger if there is a sudden stop or reversal?

"While the trend toward longer-term investment in emerging markets is likely to continue, shocks to

growth prospects or other drivers of private investment could lead to large investment reversals. The

structural trend of investing in emerging market assets accelerated following the crisis, driven mostly by relatively good economic and investment outcomes. Still, the sensitivity analysis in this chapter showed that a negative shock to growth prospects in emerging markets could potentially lead to flows out of emerging market equities and bonds. These flows could reach a scale similar to—or even larger than—the outflows these countries experienced during the financial crisis. ... Policymakers should prepare for the possibility of a pullback from their markets in order to mitigate the risk of potentially disruptive liquidity problems, especially if market depth may not be sufficient to avoid large price swings. Emerging market policymakers ... should prepare contingency plans to maintain liquidity in asset markets during periods of market turmoil, perhaps using sovereign asset managers as providers of liquidity as other investors exit, as some did during the crisis ...

Will countries start taking more risk with foreign exchange reserves?

"As heightened risk awareness and regulatory initiatives push private investors to hold “safer” assets, sovereign asset managers may take on some of the longer-term risks that private investors now avoid. ... However, global foreign exchange reserve holdings (excluding gold) have grown so fast in recent

years that their size for many countries now exceeds that needed for balance of payments and monetary purposes. ... Therefore, an increasing share of reserves could be available for potential investment in less liquid and longer-term risk assets. A new IMF estimate puts core reserves needed for balance of payments purposes in emerging market economies at $3.0–$4.4 trillion, leaving $1.0–$2.3 trillion potentially available to be invested beyond the traditional mandate of reserve managers, in a manner more like that of SWFs."

What about sovereign wealth funds?

"Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) hold some $4.7 trillion in assets ... while international foreign exchange reserves amount to $10 trillion. Taken together, the value of assets in SWFs and foreign exchange reserves is equal to about one-fourth of the assets under management of private institutional investors. ..."

0

comments

Labels:

international finance

Can You Push on a String? Should You?

It has been a commonplace observation about monetary policy for decades that "you can't push on a string." That is, while monetary policy can definitely slow down an economy during an inflationary period by using higher interest rates, it may no work as well to use low interest rates to stimulate an economy during a period of high unemployment. The problem is that although a central bank can make reserves available to banks, it cannot force banks to want to lend nor households and firms to want to borrow.

However, some would argue that we haven't yet pushed hard enough or long enough. As I will explain, I'm dubious about this argument. But for an example, Charles L. Evans, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, gave a talk on September 7 advocating a more aggressively expansionary monetary policy in "The Fed's Dual Mandate Responsibilities and Challenges Facing U.S. Monetary Policy." Here is some of the flavor of his argument:

As I read it, Evans's argument is based on two claims: 1) A truly aggressive monetary policy could bring down the unemployment rate; and 2) The costs of continued high unemployment are enormous, and the risk of significantly higher inflation is low, so uncertainty should be resolved in favor of a more aggressive monetary policy. I am dubious of both these claims.

Will a more aggressive monetary policy reduce unemployment?

Evans implies that the Federal Reserve hasn't really done all that much to fight unemployment: he says that if inflation were up, central bankers "would be acting as if their hair were on fire," and says that similar urgency is needed in fighting unemployment.

It seems to me that the Fed has been acting as if its hair was on fire! If you had asked me, circa 1986 or 1996 or 2006, about how I would describe a Federal Reserve which dropped the federal funds rate to near-zero, held it there for three years (since late 2008), and promises to keep it there for another two years (as it did at its August meeting of the Open Market Committee), and at the same time creating money to buy a couple of trillion dollars worth of federal debt and mortgage-backed securities, I would called it an extraordinarily and unimaginably extreme monetary policy. I have supported that extreme reaction, given the extreme circumstances of the U.S. economy in late 2008 and into 2009. But to claim that the Fed hasn't been very aggressive in fighting unemployment is ridiculous.

Milton Friedman once famously said: "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." At this point, the argument in favor of a more aggressive monetary policy comes close to making the extraordinary claim: "Unemployment is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." But is it always possible to fix unemployment with an appropriately strong dose of monetary policy? The answer seems obviously "no." Unemployment is sometimes rooted in structural characteristics of an economy as it slowly adjusts to a severe negative shock.

Evans talks about whether the Fed should move to targeting the price level, or to targetting a level of nominal GDP. Whatever the theoretical arguments for such steps, the Fed's extreme easing has been unable to push up inflation substantially. The central bank certainly seems to have been pushing on a string. And we have the looming example of Japan, where the central bank has been running a near-zero target interest rate for almost 15 years at this point, without successfully stimulating a higher price level. The Fed has already promised to extend the near-zero federal funds interest rate for two years. I just don't believe that promising to keep it there indefinitely, until unemployment falls, is the magic key to stimulating economic recovery.

It doesn't seem pragmatic to say that highly expansionary Fed policies for about four years, since late 2007, haven't worked to reduce unemployment or to create a higher price level, so we must continue those same policies of near-zero interest rates indefinitely. In a previous blog post about a month ago, "Can Bernanke Unwind the Fed's Policies?" , I offered an overview of what the Fed has done and raised some of these issues.

Is there little risk to pursuing an even more aggressive monetary policy?

Sustained high unemployment is a terrible social illness. If it's true that an aggressive monetary policy might help, and at least would be unlikely to harm, then there would be a case for proceeding. But there is at least some chance that harm is being done. Here are three possible risks:

1)What if inflation remains bottled up for some time, but then arrives very quickly over a few months? Or what if the U.S. dollar begins to sink in value very rapidly? After all, we have no real experience with the kind of monetary policy we are conducting. A burst of high and sustained inflation would mean that all the banks and financial institutions which have been holding low-interest debt from the last few years would face huge losses on their portfolios. The Federal Reserve would face such losses on its holdings of debt, too.

2) When the Fed engages in quantitative easing, it is essentially using its power to create money as a way of financing federal government borrowing and mortgage-backed lending. In the middle of the financial crisis in late 2008 and early 2009, this step made sense to me. But if this policy is extended over a period of years, well after the actual financial crisis has ended, surely these trillion-dollar interventions have some possibility of creating lasting distortions in the housing market or in markets for government debt?

3) Perhaps most concerning, the aggressive monetary policy of near-zero interest rates may be locking the economy into slow growth. James Bullard is president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, wrote about this about a year ago in an article called "Seven Faces of `The Peril'".

Bullard argues that there may be two stable equilibria with regard to monetary policy: One equilibrium involves an inflation rate around 2-3% and a nominal interest rate that is slightly higher. This was the situation in the U.S. economy for much of the 2000s, before the financial crisis. The other equilbrium involves an inflation rate of near-zero and nominal interest rates of near-zero. This has been the situation of Japan in the last 15 years or so, and arguably, it is the situation in which the U.S. now finds itself.

Bullard argues that in this situation, the central bank never raises the interest rate, because inflation is low, but it also can't lower the interest rate, because that rate is already near-zero. Thus, the interest rate stops being a tool of monetary policy, and instead is passive and useless. He writes of this situation: "The policymaker is completely committed to interest rate adjustment as the main tool of monetary policy, even long after it ceases to make sense (long after policy becomes passive), creating a second steady state for the economy. Many of the responses described below attempt to remedy the situation by recommending a switch to some other policy when inflation is far below target. The regime switch required must be sharp and credible— policymakers have to commit to the new policy

and the private sector has to believe the policymakers."

Bullard's suggested policy response is to expand quantitative easing by having the Fed purchase additional Treasury securities, but also to get the interest rate back up. He writes:

However, some would argue that we haven't yet pushed hard enough or long enough. As I will explain, I'm dubious about this argument. But for an example, Charles L. Evans, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, gave a talk on September 7 advocating a more aggressively expansionary monetary policy in "The Fed's Dual Mandate Responsibilities and Challenges Facing U.S. Monetary Policy." Here is some of the flavor of his argument:

"Suppose we faced a very different economic environment: Imagine that inflation was running at 5% against our inflation objective of 2%. Is there a doubt that any central banker worth their salt would be reacting strongly to fight this high inflation rate? No, there isn’t any doubt. They would be acting as if their hair was on fire. We should be similarly energized about improving conditions in the labor market. ...

It is painfully obvious that the large quantities of unused resources in the U.S. are an enormous waste. And it’s not just the current loss—over substantial periods of time, the skills of long-term unemployed workers decline, their re-employment prospects for similar jobs fade, and these reductions in skills have a lasting effect on the future growth potential of the economy. ...

One way to provide more [monetary] accommodation would be to make a simple conditional statement of policy accommodation relative to our dual mandate responsibilities. ... This conditionality could be conveyed by stating that we would hold the federal funds rate at extraordinarily low levels until the unemployment rate falls substantially, say from its current level of 9.1% to 7.5% or even 7%, as long as medium-term inflation stayed below 3%. ... [I]t would not be unreasonable to consider an even lower unemployment threshold that would be enough progress to justify the start of policy tightening. There are other policies that could give clearer communications of our policy conditionality with respect to observable data. For example, I have previously discussed how state-contingent, price-level targeting would work in this regard. Another possibility might be to target the level of nominal GDP, with the goal of bringing it back to the growth trend that existed before the recession."

As I read it, Evans's argument is based on two claims: 1) A truly aggressive monetary policy could bring down the unemployment rate; and 2) The costs of continued high unemployment are enormous, and the risk of significantly higher inflation is low, so uncertainty should be resolved in favor of a more aggressive monetary policy. I am dubious of both these claims.

Will a more aggressive monetary policy reduce unemployment?

Evans implies that the Federal Reserve hasn't really done all that much to fight unemployment: he says that if inflation were up, central bankers "would be acting as if their hair were on fire," and says that similar urgency is needed in fighting unemployment.

It seems to me that the Fed has been acting as if its hair was on fire! If you had asked me, circa 1986 or 1996 or 2006, about how I would describe a Federal Reserve which dropped the federal funds rate to near-zero, held it there for three years (since late 2008), and promises to keep it there for another two years (as it did at its August meeting of the Open Market Committee), and at the same time creating money to buy a couple of trillion dollars worth of federal debt and mortgage-backed securities, I would called it an extraordinarily and unimaginably extreme monetary policy. I have supported that extreme reaction, given the extreme circumstances of the U.S. economy in late 2008 and into 2009. But to claim that the Fed hasn't been very aggressive in fighting unemployment is ridiculous.

Milton Friedman once famously said: "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." At this point, the argument in favor of a more aggressive monetary policy comes close to making the extraordinary claim: "Unemployment is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." But is it always possible to fix unemployment with an appropriately strong dose of monetary policy? The answer seems obviously "no." Unemployment is sometimes rooted in structural characteristics of an economy as it slowly adjusts to a severe negative shock.

Evans talks about whether the Fed should move to targeting the price level, or to targetting a level of nominal GDP. Whatever the theoretical arguments for such steps, the Fed's extreme easing has been unable to push up inflation substantially. The central bank certainly seems to have been pushing on a string. And we have the looming example of Japan, where the central bank has been running a near-zero target interest rate for almost 15 years at this point, without successfully stimulating a higher price level. The Fed has already promised to extend the near-zero federal funds interest rate for two years. I just don't believe that promising to keep it there indefinitely, until unemployment falls, is the magic key to stimulating economic recovery.

It doesn't seem pragmatic to say that highly expansionary Fed policies for about four years, since late 2007, haven't worked to reduce unemployment or to create a higher price level, so we must continue those same policies of near-zero interest rates indefinitely. In a previous blog post about a month ago, "Can Bernanke Unwind the Fed's Policies?" , I offered an overview of what the Fed has done and raised some of these issues.

Is there little risk to pursuing an even more aggressive monetary policy?

Sustained high unemployment is a terrible social illness. If it's true that an aggressive monetary policy might help, and at least would be unlikely to harm, then there would be a case for proceeding. But there is at least some chance that harm is being done. Here are three possible risks:

1)What if inflation remains bottled up for some time, but then arrives very quickly over a few months? Or what if the U.S. dollar begins to sink in value very rapidly? After all, we have no real experience with the kind of monetary policy we are conducting. A burst of high and sustained inflation would mean that all the banks and financial institutions which have been holding low-interest debt from the last few years would face huge losses on their portfolios. The Federal Reserve would face such losses on its holdings of debt, too.

2) When the Fed engages in quantitative easing, it is essentially using its power to create money as a way of financing federal government borrowing and mortgage-backed lending. In the middle of the financial crisis in late 2008 and early 2009, this step made sense to me. But if this policy is extended over a period of years, well after the actual financial crisis has ended, surely these trillion-dollar interventions have some possibility of creating lasting distortions in the housing market or in markets for government debt?

3) Perhaps most concerning, the aggressive monetary policy of near-zero interest rates may be locking the economy into slow growth. James Bullard is president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, wrote about this about a year ago in an article called "Seven Faces of `The Peril'".

Bullard argues that there may be two stable equilibria with regard to monetary policy: One equilibrium involves an inflation rate around 2-3% and a nominal interest rate that is slightly higher. This was the situation in the U.S. economy for much of the 2000s, before the financial crisis. The other equilbrium involves an inflation rate of near-zero and nominal interest rates of near-zero. This has been the situation of Japan in the last 15 years or so, and arguably, it is the situation in which the U.S. now finds itself.

Bullard argues that in this situation, the central bank never raises the interest rate, because inflation is low, but it also can't lower the interest rate, because that rate is already near-zero. Thus, the interest rate stops being a tool of monetary policy, and instead is passive and useless. He writes of this situation: "The policymaker is completely committed to interest rate adjustment as the main tool of monetary policy, even long after it ceases to make sense (long after policy becomes passive), creating a second steady state for the economy. Many of the responses described below attempt to remedy the situation by recommending a switch to some other policy when inflation is far below target. The regime switch required must be sharp and credible— policymakers have to commit to the new policy

and the private sector has to believe the policymakers."

Bullard's suggested policy response is to expand quantitative easing by having the Fed purchase additional Treasury securities, but also to get the interest rate back up. He writes:

"The United States is closer to a Japanese-style outcome today than at any time in recent history. In part, this uncomfortably close circumstance is due to the interest rate policy now being pursued by the FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee]. That policy is to keep the current policy rate close to zero, but in addition to promise to maintain the near-zero interest rate policy for an “extended period.” But it is even more than that: The reaction to a negative shock in the current environment is to extend the extended period even further, delaying the day of normalization of the policy rate farther into the future.I haven't figured out whether I believe the Bullard-style model. In the U.S., we don't have enough experience with a near-zero federal funds interest rate to be highly confident about what will happen. But it is at least possible that those who advocate extending near-zero interest rates are doing more to trap the U.S. economy in Japan-style stagnation than to stimulate a robust recovery.

Promising to remain at zero for a long time is a double-edged sword. ... Under current policy in the United States, the reaction to a negative shock is perceived to be a promise to stay low for longer, which may be counterproductive because it may encourage a permanent, low nominal interest rate outcome. A better policy response to a negative shock is to expand the quantitative easing program through the purchase of Treasury securities."

0

comments

Labels:

monetary policy

Is the Great Depression is the Right Analogy for the Great Recession?

Barry Eichengreen delivered the Presidential Address to the Economic History Association,

"Economic History and Economic Policy," which is available at his website. He begins (footnotes omitted):"This has been a good crisis for economic history. It will not surprise most members of this audience to learn that there was a sharp spike in references in the press to the term "Great Depression" following the failure of Lehman Bros. in September of 2008. More interesting is that there was also a surge in references to "economic history," first in February of 2008, with growing awareness that this could be the worst recession since you know when, and again in October, coincident with fears that the financial system was on the verge of collapse. Journalists, market participants, and policy makers all turned to history for guidance on how to react to this skein of otherwise unfathomable events."

Eichengreen discusses with care and detail whether analogies are chosen because they are the best example, or because they are a salient example almost within living memory, or because they deliver an already-selected policy conclusion. Drawing on a wide variety of political and economic examples, Eichengreen points out that since historical episodes never precisely match present events, often the most productive way to use history in making economic policy is not to use a single analogy, but instead to consider a number of somewhat relevant episodes, and to compare and contrast the events, policies, and outcomes. He makes the provocative point that the choice of analogy has a tendency to guide policy responses. In the case of the analogy from the Great Depression to the Great Recession:

"The analogy legitimated certain responses to the collapse of economic and financial activity while delegitimating others. It legitimized the notion that the Fed should respond aggressively to prevent the collapse of a few investment funds from precipitating a cascade of financial failures. This reflected the widespread currency of Friedman and Schwartz‘s interpretation of the Great Depression – that what had made the Depression great was the inadequate response of the Federal Reserve. ... The analogy with the Great Depression informed the policy response to the crisis more generally. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation increased deposit insurance coverage to $250,000 per depositor exactly one day after press references to the Great Depression peaked. The action was presumably informed by the view of the banking panics of the Great Depression as runs by uninsured depositors, and the historical interpretation, widely shared, that those panics had played a key role in the contraction of the money supply and the impairment of the payments system. The analogy with the Great Depression similarly lent legitimacy to the argument that the Congress and Administration should respond with fiscal stimulus. This reflected the "lesson" of history that the depth and duration of the Depression were attributable in no small part to the fact that fiscal stimulus was not used to counter the collapse of private demand. ...

The analogy with the Great Depression also delegitimized the temptation to respond with protectionist measures designed to bottle up the remaining demand. This reflected the lesson, widely taught to undergraduates and invoked by policy makers, that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff aggravated the crisis of the 1930s. In fact, this "lesson" of history is not supported by modern research, which concludes that Smoot Hawley played at most a minor role in the propagation of the Depression."

Eichengreen points out that these policy lessons are not the only possible lessons from the Great Depression, and that choosing other historical episodes might have emphasized other lessons.

"Did we need a new Neal Deal? Well, that depended on whether you sided with historians who argue that the New Deal helped to end the Depression or only prolonged it. Did we need a jolt to the exchange rate to vanquish deflationary expectations? The answer depended on whether your view was that Roosevelt‘s decision to take the U.S. off the gold standard in 1933 was the critical decision that transformed expectations and ended deflation or whether you thought it was a sideshow. For those attempting to move from metaphor to analogy, this was a reminder that the distilled, authoritative incapsulation of the period remains a work in progress.Eichengreen also makes the point that the connection from past to present also works in reverse: for example, current economic events will alter our historical understanding of the policy reactions to the Great Depression.

Although the Great Depression was clearly the dominant base case in discussions of the 2008-9 crisis, there were other possible analogies. There was the 1873 crisis, driven by an investment boom and bust like that of the period leading up to 2007, which led to the failure of brokerage houses, in parallel with the problems in 2008 of the investment banks. There was the 1907 crisis, in response to which J.P. Morgan organized a lifeboat operation that resembled in important respects the 2008 rescue of Bear Stearns by none other than JP Morgan & Co."

"The mainstream narrative is that the experience of the Depression led to a series of institutional and policy innovations making it less likely that something similar thing would happen again. American economic historians refer in this connection to federal deposit insurance, unemployment insurance, Social Security, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the concentration of monetary-policy-making authority at the Federal Reserve Board, and automatic fiscal stabilizers. Historians of other countries have similar list. Although the stabilizing impact of particular entries on these lists has been disputed, the thrust of the dominant narrative is clear.

We now have had a graphic reminder that we have less than fully succeeded in corralling threats to economic and financial instability. While policy responses may avoid the repetition of past threats, they are no guarantee against future threats. Markets tend to adapt to stabilizing policy innovations in ways that render those innovations less stabilizing. As memories of the earlier crisis fade, policy makers themselves become more likely to consort with market participants in this effort. I suspect that we will now see more attention to these longer-term adaptations to the legacy of the Great Depression and less to the short-term policy response."

0

comments

Labels:

Great Depression,

history

U.S. Poverty by the Numbers

Each September the U.S. Census Bureau releases an annual report on the U.S. poverty rate. Each year, the report is grist for the media mill for a few days, with arguments that the official poverty rate overstates or understates "true" poverty. But at least in the days right after the poverty numbers come out, I prefer not to perform in this annual dance of the definitions. Here, I'll make four more basic points, with minimal editorializing: 1) Show the 2010 poverty thresholds and trends over recent decades; 2) Show how poverty has come to affects the young more than other age groups; 3) Show the drop in median household income not just since the start of the recession in 2007, but back to 1999; and 4) Preview an argument about definitions of poverty that is coming next month.

1) The 2010 poverty thresholds and trends over recent decades

The poverty rate is based on money income. As the report explains: " If a family’s total money income is less than the applicable threshold, then that family and every individual in it are considered in poverty. The official poverty thresholds are updated annually for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U). The official poverty definition uses money income before taxes and tax credits and excludes capital gains and noncash benefits (such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits and housing assistance). The thresholds do not vary geographically." The poverty thresholds are adjusted for household size and for number of children in the household. Here they are for 2010:

As an economist, I lack any talent for drama. But I do sometimes try to give a little life to the poverty thresholds by pointing out that the poverty line for a three-person household with two children is $17,568. Divide that by 365 days in a year, and by three people per meal. It's about $16 in total consumption per person per day. There are high-end restaurants in most U.S. cities where $16 will buy you a fancy appetizer. The share of the population below this poverty line--the "poverty rate"-- dipped in the 1960s, but since the 1970s has hovered between about 12-15% of the population.

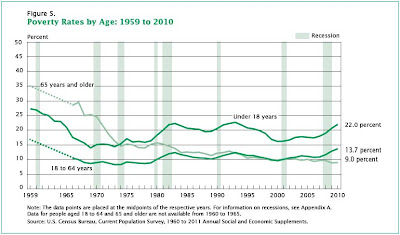

2) How poverty has come to affects the young more than other age groups

In the early 1960s, poverty was more prevalent among the elderly. But in the early 1970s, the poverty rate for the elderly dropped below that for those in the under-18 age group. From the mid 1980s up to about 2000, poverty rates for the elderly were similar to those for the age 18-64 population. Since about 2001, poverty rates for the elderly have been below those for the 18-64 age group. Currently, the poverty rate for those over 65 is 9.3%; for the 18-64 age group, 13.7%; for those under 18, 22%. As we discuss the problems of our aging society and how we have set up Social Security and Medicare systems whose current financing will not be able to deliver the promised benefits, it's worth remembering that more than a fifth of those under age 18 are living in households below the poverty line.

In fact, the closer you go to the poverty line, and below the poverty line, the more the under-18 population is overrepresented. Specifically, those under age 18 are 24.4% of the total population; 31.3% of the population with income below 200% of the poverty threshold; and 35.5% of the population below 100% of the poverty threshold.

3) Median household income has dropped not just since the start of the recession in 2007, but compared to 1999

The median household is the household where half of all households have more money income and half have less: that is, the household at the 50th percentile of the income distribution. Income gains for those at the top of the income distribution affect average income, but they do not affect median income. The report points out: "Real median household income was $49,445 in 2010, a 2.3 percent decline from 2009 ... Since 2007, median household income has declined 6.4 percent (from $52,823) and is 7.1 percent below the median household income peak ($53,252) that occurred in 1999 ..." Here's the figure:

4) A Preview of a Coming Debate over the Supplemental Poverty Measure

The Census Bureau is of course perfectly aware of the disputes over how poverty should be measured, and has long offered alternative measures of poverty for those who took the time to read the fine print. Back in 1995, there was a big National Academy of Sciences report on ways of measuring poverty. In October, the Census Bureau is planning to come out with a measure of poverty that is more closely linked to actual consumption: